I’m a big fan (okay, I’ve listened to every episode) of “How I Built This” by Guy Raz—a popular podcast about how famous entrepreneurs established and grew their businesses. The first-hand stories of how these people earned their success are always filled with great insights that I enjoy thinking about and even apply in my role as a leader.

If you're a listener, too, you know that Guy asks every guest the same question at the end of the show: How much of their success do they attribute to luck, and how much to hard work?

The answers are always interesting. Not necessarily because each one blueprints some kind of golden ratio for success (although it’s tempting to consider that), but because it reveals a deeper, perhaps unintentional insight into a particular entrepreneur’s journey and their own personal perspective about what success takes.

As you can imagine, the answers are as varied as the people they’re posed to and the industries they work in. But with more than 300 episodes recorded, I’ve always wondered if there was something more profound to be learned from these answers. Would we learn that most entrepreneurs consider themselves more lucky than hard working? Was it the other way around? Or was there something completely different to learn altogether?

Doing the math

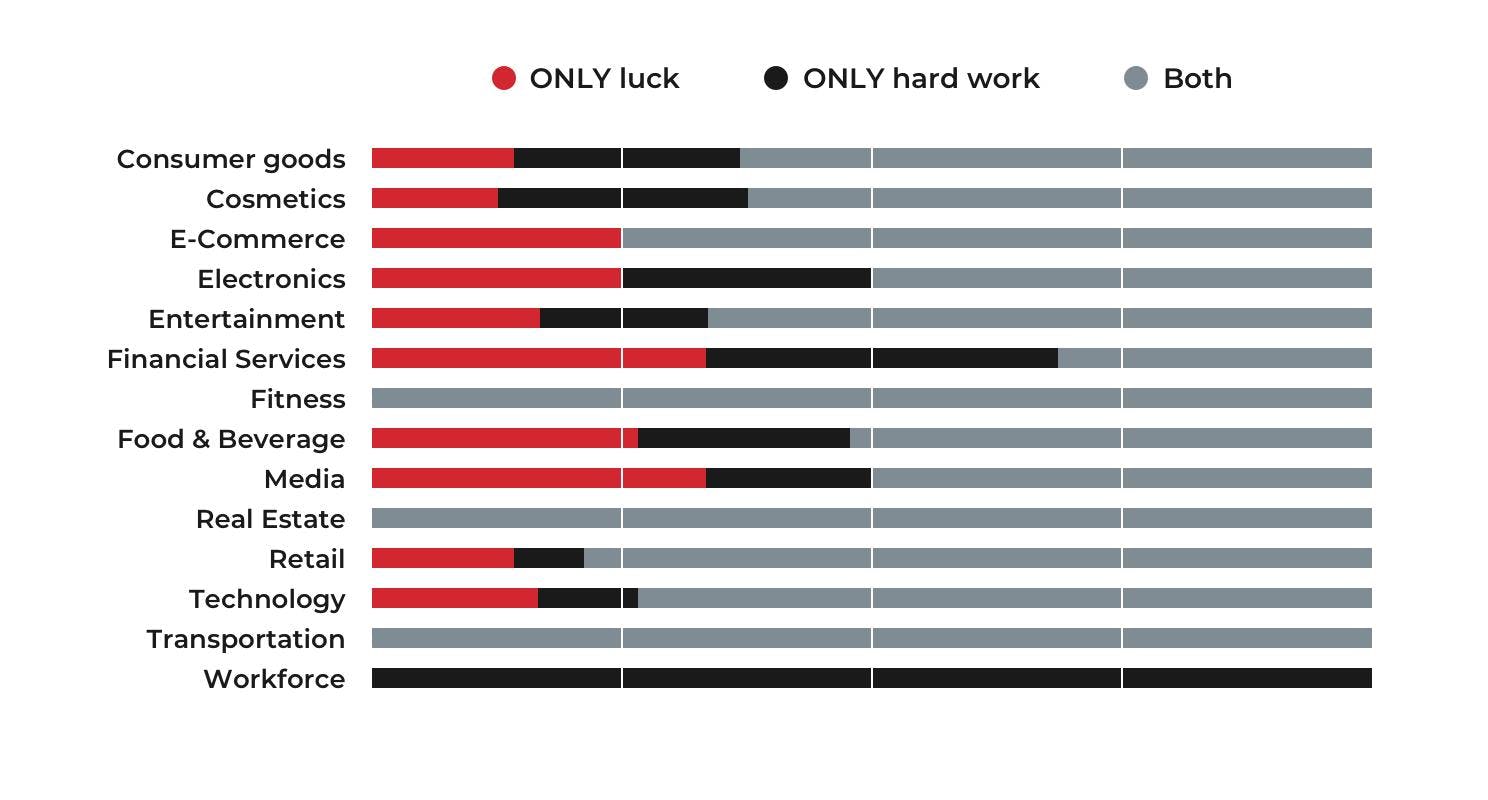

We transcribed every single episode and broke down the responses by entrepreneurs in every industry, plus came up with overall averages to see what that data tells us. Overall averages:

- 64% (81/ 127) of guests said both luck and hard played a role in their success.

- 19% (24/127) of episodes said ONLY luck was at play.

- Only 17% of guests didn’t consider luck as part of their success.

- 83% of guests acknowledged that luck has played a role in their success in some capacity.

Broken down by industry:Note: sample sizes vary between industry.

>>>Dig into the data here<<<That’s all quite interesting. Especially when you consider the perspectives of those who believe their success is attributable to only one or the other. But as I thought about these numbers and how to interpret them, something nagged at me. I kept coming back to a pretty basic but big question:

What is “luck,” anyway?

How do we define it in a useful way? Merriam Webster says luck is:

- A force that brings good (fortune?) or adversity

- Events or circumstances that operate for or against an individual

By that definition, luck is something out of our control. Luck is where, to whom, and when you were born. Luck is the incalculable way the cards fall. Luck could even be considered privilege.

(Note: It’s impossible to speak about success, luck, and hard work without acknowledging the role that privilege plays in it. I acknowledge my privilege: I know that I’ve had opportunities that others haven’t.) As Malcolm Gladwell pointed out in Outliers, Bill Gates and the Beatles were “lucky” to have access to the tools they did, in the time and place they did. And of course they worked hard to earn their successes.

But what about the intangibles, or unpredictable factors? The teachers that agreed to let Bill stay late in the lab cause they liked him. Or the opportunities and/or relationships that John, Paul, George, and Ringo sacrificed before a promoter or booking agent or record label took notice of them? Is there more to it than being in the right place at the right time?

It’s certainly conceivable that there existed other children who were as, if not more, intelligent as Bill—and had access to similar technology. There were almost certainly other musicians who possessed a similar calibre of talent, in the same era, and with access to similar venues and performance opportunities as The Beatles. But despite most things being theoretically equal, they did not achieve the same levels of success.

If luck, as we understand it, is something that’s outside of our control, are we focusing on the wrong thing? Is there something else that goes into this elusive cocktail of success that is neither luck or hard work?

I think there’s something else at work here—something that I’m going to argue is actually more important.

The humdrum of everyday life

This missing part of the equation is the stuff that is as seemingly insignificant as our many daily interactions and as important as the relationships we build over the span of our lives and careers. It’s as much the failures we learn from as the successes we build on. It’s the outcome of every decision we make, big and small. It exists in front of us right now as well as in life’s periphery—but it’s always present.

A very basic example to clearly illustrate the point: consciously choosing to eat a nutritious, calorically balanced food item instead of a sugary one would be making a decision that has a small but very real impact. The scope of that impact can drastically change depending on if that decision is made habitually. Repeated many times over, it’s easy to see how each choice creates vastly different outcomes.

But luck was not involved. Hard work was not involved. A simple A or B decision made this happen.

This line of thinking can be applied in ways that are far more complex and difficult to measure than the above example. Like an underpaid job that led to other more gainful opportunities. Or the event you agreed to attend on a whim, where you ended up meeting the person who would become your lifelong partner.

Here’s an example of my own experience. Early in my entrepreneurship career, I discovered a competitor who was, as far as I could tell, doing better than I was. So I decided to reach out to them to see if I could buy them (I did not have the money to buy them). This led to a series of back-and-forth emails, a conversation over coffee, and what eventually turned into the acquisition of my business instead.

Neat, right? But the story doesn’t end there.

The person who ran the company that acquired mine is Tobyn Sowden, the now-CEO of Redbrick and my current business partner. The act of sending one email eventually resulted in a long-lasting and successful business relationship and friendship.

It wasn’t luck. It wasn’t hard work. It was something entirely different—what I like to call increasing the surface area of opportunity.

Think about how many small decisions have eventually led to something bigger and better. Most of them, however small, gained interest over time and made an impact in your life.

Increasing the surface area of opportunity

What happens when you apply that mindset to your everyday decisions? You start making choices that are more likely to create better outcomes. You climb the stairs instead of the elevator. You take public speaking classes. You agree to do things you probably wouldn’t have before. Suddenly, doors open and opportunities arise—these decisions start revealing themselves as the best source of “luck” one can experience. Only it’s not luck. Because you probably had some degree of input and control over the decision or the act.

How I increase my surface area of opportunity

Arriving at this conclusion has shaped the way I think about many things. Mostly, in my role as CMO at Redbrick. But it extends to my family, my friends, and everything in-between. So how do I go about making that surface area bigger? It boils down to a few pretty simple things.

I’m curious. I ask questions about things I don’t fully understand—even if the question seems basic. This has exposed me to so many different ideas and concepts that would have likely continued flying over my head for years. It has enriched my grasp of both complex topics and even simple ones that live outside of my wheelhouse. I like to think it encourages others to do the same, too.

I say yes as often as I possibly can. I do things I wouldn’t normally do—especially if they scare me. And I try to help people even when it’s not always convenient. This has allowed me to better understand what my teams do day-to-day and many of the challenges they face that I wouldn’t normally have visibility into. I’ve had incredible experiences, learned new things, gained empathy, and met new and interesting people. Just by saying yes more often.

I try to be present for every decision I make, however small, as an opportunity to do something that can improve outcomes for the people I lead, my family, and of course, myself. Turning off auto-pilot and tuning in, even for just a moment, can change everything from what kind of day you have to the outcome of any given situation.

One might even call it creating your own luck.

Defining success differently

Despite how much I enjoy the stories of success and entrepreneurship I hear on HIBT—and I’ll always listen right to the end to hear every guest’s answer to Guy’s final question—I’m beginning to think we need to start thinking about success in different terms.

Success isn’t as binary as the equation of luck and hard work. Sure, they both play a role in it. In some cases, more than others. But they don’t tell the whole story, and as a result we could be selling ourselves short because we may have more input into and control over outcomes than we’re giving ourselves credit for.

Perhaps by acknowledging the many other small and large factors that go into success—or increasing your surface area of opportunity—we can help others better understand it and set them up to achieve it.